Our Beautiful Bay

“The Bay is a once-in-a-career project, and it is so wonderful to work with people who want to do everything right.” – Penny Cutt, Cummins Cederberg

I was fortunate to grow up in and around Sarasota Bay. Whether my family and I were out shelling, fishing or just enjoying a day on our boat, skimming over the beautiful bay waters, Sarasota Bay was an important part of my childhood.

While it is still incredibly beautiful, over the years I have watched the bay’s ecology change, to the point that today, according to Penny Cutt of Cummins Cederberg, it is listed as “an impaired body of water” by the state of Florida.

That doesn’t mean our beautiful bay can’t be saved. Indeed, increased awareness of the danger of runoff and sea-level rise is already making a difference. And projects such as The Bay, Sarasota’s 53-acre waterfront park, will significantly brighten Sarasota Bay’s ecological future.

I talked with Penny Cutt of Cummins Cederberg, a coastal engineering firm that focuses on water-based coastal projects, such as marinas, waterfront parks, and beach renourishment, about how The Bay will make an ecological difference here on the Gulf Coast.

Cutt has been in South Florida, namely Fort Lauderdale, since she was six months old. She attended college at The University of Florida and did her graduate work at Nova Southeastern. “By training,” she said, “I’m a marine ecologist.” She started her career with Dade County’s environmental department, permitting single-family docks and marinas. From there she moved on to the Southwestern Florida Management District, where she worked in enforcement. She was then hired by the Army Corps of Engineers, mainly for her background in coastal issues. All of which, she said, prepared her to enter the consulting world.

“I joined a firm where I stayed for nine years and learned the ins and outs of the consulting industry. When a couple of the directors left, I knew it was time for a change. That’s when I joined Cummins Cederberg.”

“We do a lot of resiliency work, looking at parks and waterfront properties and figuring out how we can renovate seawalls and bulkheads, many of which were constructed in the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s, with a 30-to-50-year life span. Though we have put band-aids on most of those structures, we are now at a point where they are significantly beyond their design life and need to be replaced. We have to do this as sea level continues to rise unless we want a lot of things to be under water, especially here in Florida.

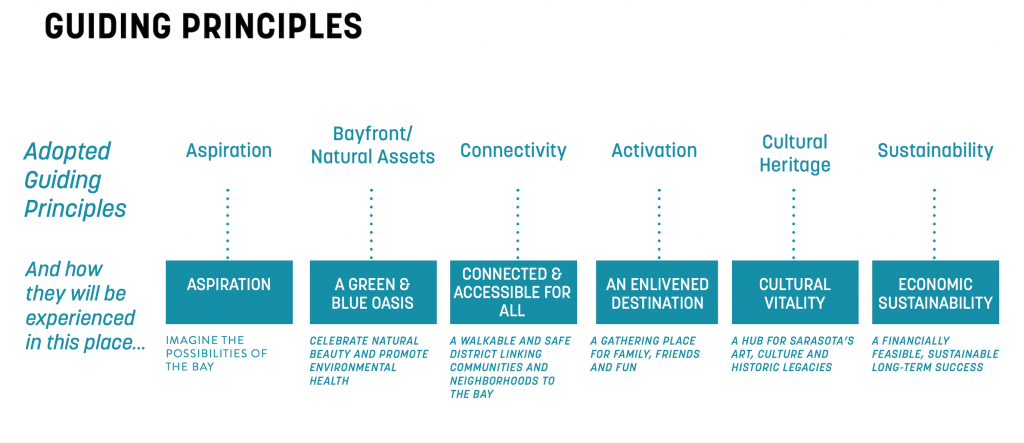

“My role with The Bay is as an environmental consultant. We are doing all of the biological monitoring and the environmental permitting to guide the team on ways to make The Bay an ecologically friendly, permittable project. We are also committed to The Bay’s resiliency, its environmental sustainability, and the educational aspects of the project.

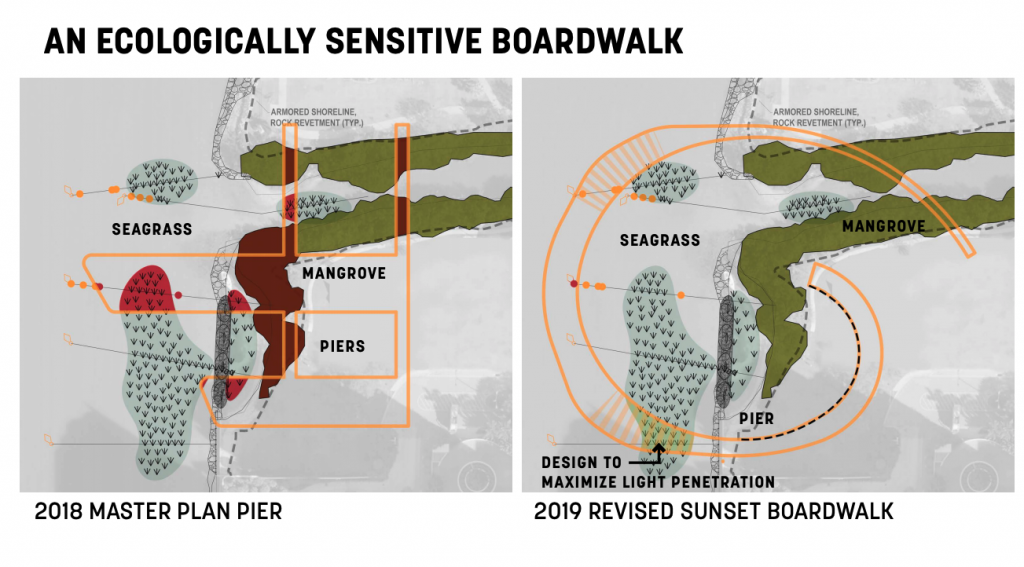

Her work began when she was asked by one of the engineers on the team to provide a seagrass survey – to basically assess what was out there. There were overwater structures (such as the Sunset Boardwalk on the southern end of the property) being planned in an environmentally sensitive area, so we needed to know where the natural resources were located.

Cutt and her team came in and performed their seagrass survey in 2018 and found a lot of seagrass and coral out there. They came back and told The Bay that the design presented in the master plan was going to have to change. “They immediately asked what they needed to do, and how they needed to do it,” Cutt said. “Working with The Bay’s design team was so phenomenal because they are just so creative,” she said.

Instead of a pier that extends straight out into the bay, the team designed a spiral-shaped pier that is narrower where it crosses the seagrasses. It also elevated the boardwalk and incorporated transparent decking that allows sunlight to penetrate so the grasses can still grow and photosynthesize.

The team also surveyed the mangroves. “Where the pier lands on the shoreline, the piles will be located so that they don’t interfere with the mangrove trunks,” Cutt explained.

Another step The Bay took is removing all of the exotic vegetation from along the shoreline. “It will allow the public to see the beauty of the area and also open it up to better wildlife utilization,” Cutt explained.

Cummins Cederberg did a follow-up survey in 2019, honing in on the Phase 1 part of the project. It focused on the coral in the area, so that any coral endangered by the pilings of the pier, for example, could be relocated.

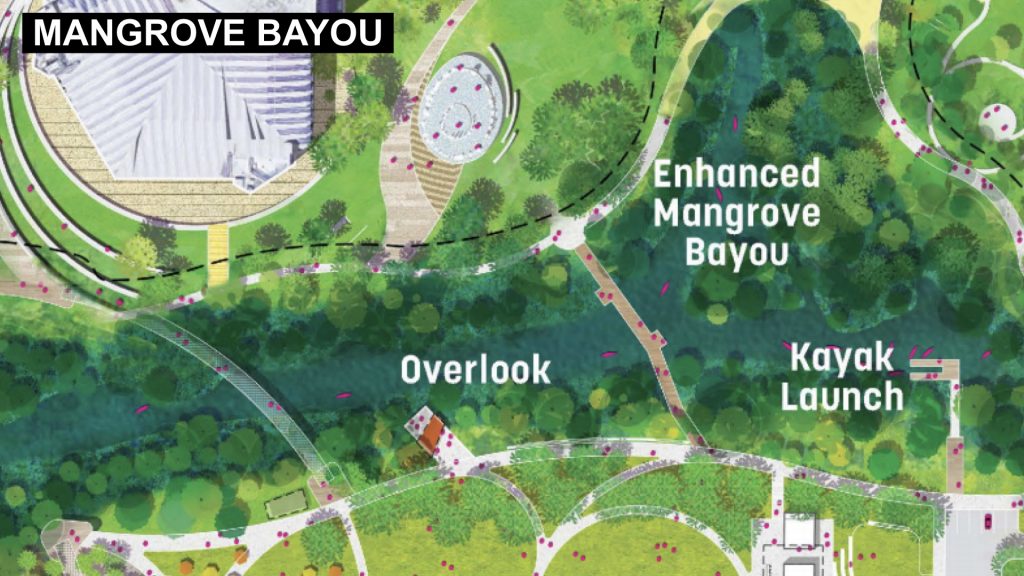

“We do the seagrass monitoring, the coral monitoring and the coral relocation,” Cutt explained. “We brought Mote Marine in to do surveys of the Mangrove Bayou area. It is filled with a lot of muck – runoff that has been accumulating for hundreds of years, making it not at all conducive to ecological colonization. So, Mote is doing surveys of what is growing in all that muck right now, and then they will do another set of surveys after the dredging is done,” Cutt said. “Recolonization is usually pretty rapid once you get all of that runoff out of there. The critters that will live in that sandy area (minus the muck) will become the main food source for snapper, grouper and other fish that will utilize that mangrove area, which also serves as the rookery for those fish, shrimp and crabs and more.

Mote Marine is also doing water-quality testing, since The Bay is going through so much effort to provide surface water treatment for the runoff. We want to document the water quality improvements. We also would like to do some fish tagging surveys. It will provide meaningful data over a long period of time about how the bay’s ecology is changing and improving.

There are two choke points that we will be opening up, so that paddleboards, kayaks and canoes can get through there – one at the mouth of the Mangrove Bayou and one at the east end. Trimming the vegetation does not adversely affect the health of the mangroves. “There will be less impact than I originally thought,” Cutt said.

Earlier this year, we did a very detailed, qualitative and quantitative survey of the seagrasses and corals in the southern third of the project area to serve as our baseline. Each year, we will be able to see how the seagrasses and corals are recovering and being enhanced by the project.

Creating a natural shoreline will also impact the area’s environmental health. Cutt explained that seawalls are hard vertical surfaces. When a wave hits it, the energy reverberates off of that wall. “It becomes like a washing machine in there,” Cutt said. “That area then can’t grow seagrasses because it is constantly being scoured by wave action. With a natural shoreline, the bumpiness of those rocks breaks up and absorbs the wave action. By putting in a natural shoreline, we create an environment that will adapt over time. It will be resilient, it’s a viable ecological habitat, it will stabilize the shoreline, and it can adapt over time, as sea levels rise.”

Cutt said she saw a lot more coral away from the shoreline than she expected to, which she described as “awesome.” “Sarasota Bay is in an urban developed area and has a lot of problems,” she said, “but there are good signs, too, like the presence of the seagrasses and corals.”

Cutt said she is especially excited about the educational aspects of The Bay. “One day, I hope to be able to take people snorkeling at The Bay,” she said. “The Sunset Boardwalk will be a seagrass classroom, where we can take kids with push nets so they can see all the creatures that live in those grassy beds. I am envisioning a lot of field trips to The Bay. It is so important that we create spaces like this where people can experience, touch and get out and enjoy these environments – so they will then want to work to protect them.” Cutt said.

About the Author: Gayle Guynup is a life-long Sarasota resident and former editor at the Sarasota Herald-Tribune, where she worked for 18 years. She now owns her own company, Content Connection, focusing on creative written content.