Timely Topics

Could The Bay actually make the bay cleaner?

Bayfront makeover to include a new filtration process for treating runoff from the 53-acre park, as well as downtown Sarasota’s streets.

NOTE: This article was originally published as a column by Carrie Seidman for Sarasota Herald Tribune on January 12, 2020.

Too often, a problem doesn’t get addressed until it’s a crisis, when resolving it is most difficult and costly. The red tide of 2018-2019 is a case in point. Though Sarasota County had for years kicked the can down the road on upgrading its water treatment systems and infrastructure, all of a sudden, water quality became an issue of the utmost urgency for politicians and residents alike.

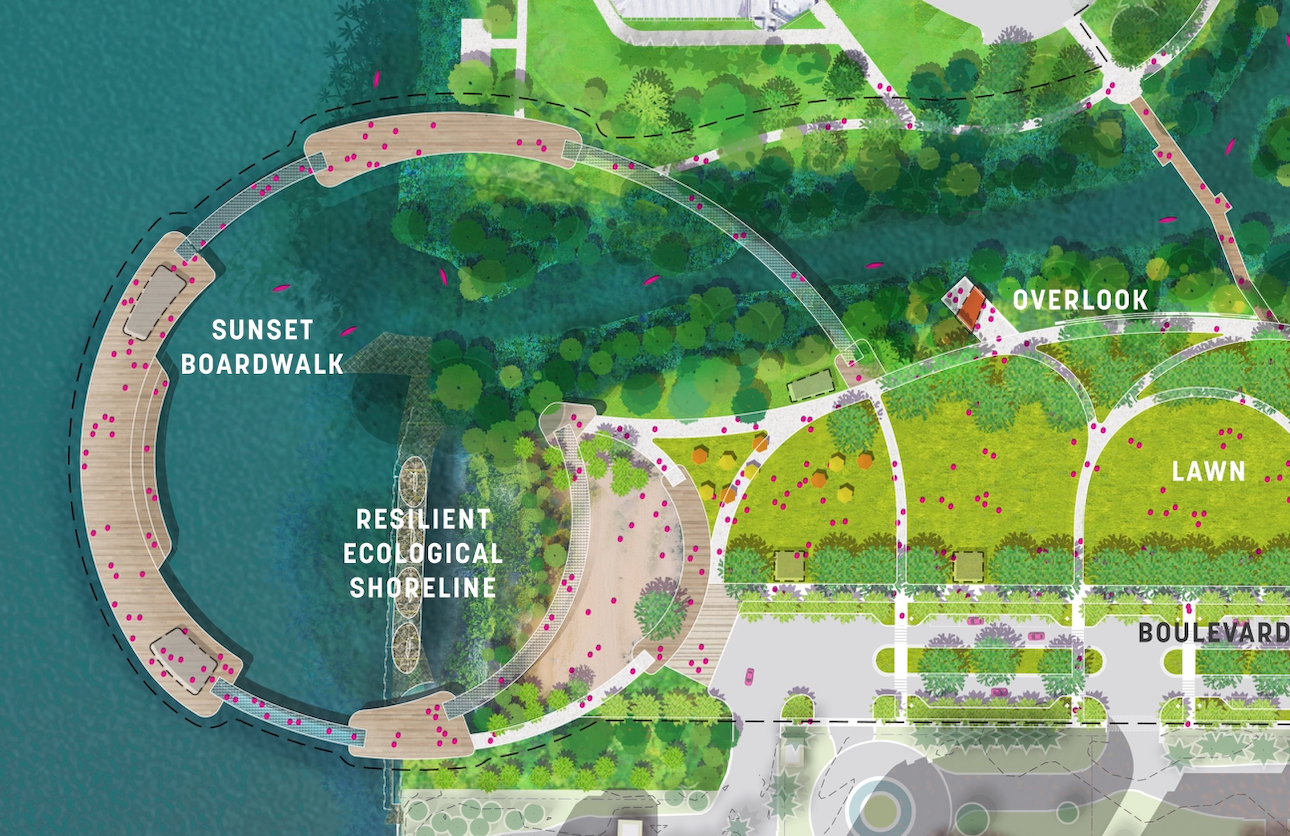

The opportunity to address a problem at the source is all too rare. Which is why a proposed water filtration system that would vastly reduce nutrient content in runoff from the 53-acre waterfront project known as The Bay — as well as from downtown Sarasota’s streets — has already gained enthusiastic support from The Bay Park Conservancy, the nonprofit START (Solutions To Avoid Red Tide) and several other environmentally-minded agencies and organizations.

The “carbon-life” process, developed by Steve Suau of Progressive Water Resources, Inc., a Sarasota hydrology company, would involve installing an underwater “barrier” made up of woodchips and “biochar” (a porous charcoal) around the lagoon inlet in Phase 1 of The Bay project. Through a natural bacterial breakdown process, the system can vastly reduce nitrogen and phosphorus in the water; in a Lakewood Ranch pilot project, the process filtered 73 percent of nitrogen and 87 percent of phosphorous out of “secondary treated” (irrigation) groundwater.

“It’s so elegant in its simplicity,” said Jon Thaxton of the Gulf Coast Community Foundation, which has granted a start-up $20,000 toward the design of a barrier for The Bay. “It’s taking all the forces Mother Nature has been using for eons and strategically configuring it for maximum efficiency, using gravity rather than mechanics or chemicals.”

Moreover, the process is “infinitely less expensive” than the cost of trying to remove nutrients once they are already in the waterway, he said.

Bill Waddill, chief implementation officer of The Bay Park Conservancy, said he was quickly sold after meeting with Suau and Sandy Gilbert, chairman and CEO of START. The filtration process fits seamlessly into The Bay’s commitment to environmental enhancement, he said, and the conservancy has already committed to digging the trench and installation of the barrier.

“I’m super excited to deploy it as part of our first phase and I’m sure we can have an impact on the water quality and the biology,” Waddill said. “And one of the things I love about it is, it’s relatively low tech and cost-effective. It’s basically a 5-by-5 trench filled with carbon materials that trigger the biology which you bury and then let nature do its thing. It’s brilliant.”

Not only would the process treat runoff from the park before it hits the bay, it could also process an estimated 15 million of untreated water that is annually dumped into the bay by six major storm water pipes that drain ground water from east of the site, Thaxton said.

“We don’t get a chance to retrofit a stormwater project of this magnitude but once or twice in a lifetime,” he said. “This will afford us the opportunity not only to treat stormwater from the site but also from the many acres of downtown Sarasota which was developed before stormwater codes were in place.”

Because of the “high profile” location and visibility of The Bay, the success of the system could elicit attention from other developers and projects looking for a low-cost and ecological way to clean up reclaimed water or stormwater, said Gilbert. And since biochar can be made from sugar cane and is also a great soil enhancement for agriculture, he even envisions convincing “big sugar” to cut down rather than burn their sugar cane and establish a biochar factory to provide product for both farmers and municipalities hoping to clean up their water systems.

Gilbert said the new process is a leap forward, but complements other programs his group has been working on since its founding in 1995. These include the GCORR (Gulf Coast Oyster Recycling and Renewal) program, which collects used oyster shells from 11 Manatee County restaurants and recycles them into reefs for live oysters, which can filter up to 50 gallons of water a day; seeding beds of clams (which have a similar filtering capacity); and installing artificial “mini-reefs” under docks. (All of these interventions are also planned for The Bay site.)

“Those programs do something positive and make a mark,” Gilbert said. “The public loves them, the government loves them because they’re self-funded. But let’s face it. What do we really want? To keep the nutrients out of the water in the first place.”

In this era of rapid growth, we’ve been tackling issues like aging infrastructure, traffic congestion and building codes when they’re bordering out of control. With the Environmental Protection Agency on the brink of declaring Sarasota Bay south of the Ringling Causeway as “nutrient-impaired,” this is an opportunity to take a proactive step before the next disastrous red tide reminder.

“People’s eyes glaze over when you talk about stormwater, it only becomes sexy once it’s in the water,” said Thaxton, a self-confessed “stormwater geek.” “But in reality, this is going to the source and using Mother Nature to turn the tides of adverse human impacts. We don’t get many chances to do this.”